# (1) 12 Oct 2016, 11:00AM: Rough Notes for New FLOSS Contributors On The Scientific Method and Usable History:

Some thrown-together thoughts towards a more comprehensive writeup. It's advice on about how to get along better as a new open source participant, based on the fundamental wisdom that you weren't the first person here and you won't be the last.

We aren't just making code. We are working in a shared workplace, even if it's an online place rather than a physical office or laboratory, making stuff together. The work includes not just writing functions and classes, but experiments and planning and coming up with "we ought to do this" ideas. And we try to make it so that anyone coming into our shared workplace -- or anyone who's working on a different part of the project than they're already used to -- can take a look at what we've already said and done, and reuse the work that's been done already.

We aren't just making code. We're making history. And we're making a usable history, one that you can use, and one that the contributor next year can use.

So if you're contributing now, you have to learn to learn from history. We put a certain kind of work in our code repositories, both code and notes about the code. git grep idea searches a code repository's code and comments for the word "idea", git log --grep="idea" searches the commit history for times we've used the word "idea" in a commit message, and git blame codefile.py shows you who last changed every line of that codefile, and when. And we put a certain kind of work into our conversations, in our mailing lists and our bug/issue trackers. We say "I tried this and it didn't work" or "here's how someone else should implement this" or "I am currently working on this". You will, with practice, get better at finding and looking at these clues, at finding the bits of code and conversation that are relevant to your question.

And you have to learn to contribute to history. This is why we want you to ask your questions in public -- so that when we answer them, someone today or next week or next year can also learn from the answer. This is why we want you to write emails to our mailing lists where you explain what you're doing. This is why we ask you to use proper English when you write code comments, and why we have rules for the formatting and phrasing of commit messages, so it's easier for someone in the future to grep and skim and understand. This is why a good question or a good answer has enough context that other people, a year from now, can see whether it's relevant to them.

Relatedly: the scientific method is for teaching as well as for troubleshooting. I compared an open source project to a lab before. In the code work we do, we often use the scientific method. In order for someone else to help you, they have to create, test, and prove or disprove theories -- about what you already know, about what your code is doing, about the configuration on your computer. And when you see me asking a million questions, asking you to try something out, asking what you have already tried, and so on, that's what I'm doing. I'm generally using the scientific method. I'm coming up with a question and a hypothesis and I'm testing it, or asking you to test it, so we can look at that data together and draw conclusions and use them to find new interesting questions to pursue.

Example:

In our coding work, it's a shared responsibility to generate hypotheses and to investigate them, to put them to the test, and to share data publicly to help others with their investigations. And it's more fruitful to pursue hypotheses, to ask "I tried ___ and it's not working; could the reason be this?", than it is to merely ask "what's going on?" and push the responsibility of hypothesizing and investigation onto others.

This is a part of balancing self-sufficiency and interdependence. You must try, and then you must ask. Use the scientific method and come up with some hypotheses, then ask for help -- and ask for help in a way that helps contribute to our shared history, and is more likely to help ensure a return-on-investment for other people's time.

So it's likely to go like this:

This helps us make a balance between person-to-person discussion and documentation that everyone can read, so we save time answering common questions but also get everyone the personal help they need. This will help you understand the rhythm of help we provide in livechat -- including why we prefer to give you help in public mailing lists and channels, instead of in one-on-one private messages or email. We prefer to hear from you and respond to you in public places so more people have a chance to answer the question, and to see and benefit from the answer.

We want you to learn and grow. And your success is going to include a day when you see how we should be doing things better, not just with a new feature or a bugfix in the code, but in our processes, in how we're organizing and running the lab. I also deeply want for you to take the lessons you learn -- about how a group can organize itself to empower everyone, about seeing and hacking systems, about what scaffolding makes people more capable -- to the rest of your life, so you can be freer, stronger, a better leader, a disruptive influence in the oppressive and needless hierarchies you encounter. That's success too. You are part of our history and we are part of yours, even if you part ways with us, even if the project goes defunct.

This is where I should say something about not just making a diff but a difference, or something about the changelog of your life, but I am already super late to go on my morning jog and this was meant to be a quick-and-rough braindump anyway...

So I'll ask a question to try and prove or disprove my hypothesis. And if you never reply to my question, or you say "oh I fixed it" but don't say how, or if you say "no that's not the problem" but you don't share the evidence that led you to that conclusion, it's harder for me to help you. And similarly, if I'm trying to figure out what you already know so that I can help you solve a problem, I'm going to ask a lot of diagnostic questions about whether you know how to do this or that. And it's ok not to know things! I want to teach you. And then you'll teach someone else.

# 15 Oct 2016, 01:55PM: New Zine "Playing With Python: Two of My Favorite Lenses":

MergeSort, the feminist maker meetup I co-organize, had a table at Maker Faire earlier this month. Last year we'd given away (and taught people how to cut and fold) a few of my zines, and people enjoyed that. A week before Maker Faire this year, I was attempting to nap when I was struck with the conviction that I ought to make a Python zine to give out this year.

So I did! Below is Playing with Python: 2 of my favorite lenses. (As you can see from the photos of the drafting process, I thought about mentioning pdb, various cool libraries, and other great parts of the Python ecology, but narrowed my focus to bpython and python -i.)

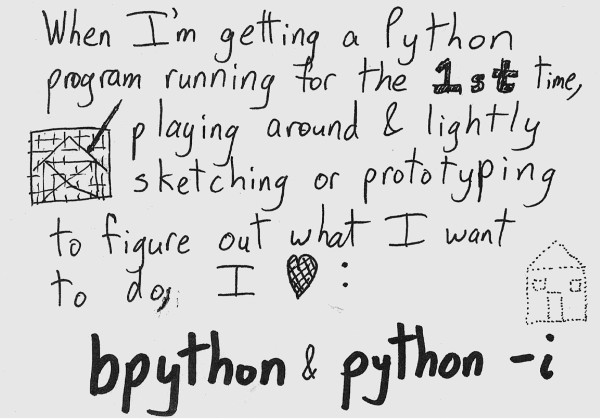

Playing with Python When I'm getting a Python program running for the 1st time, playing around & lightly sketching or prototyping to figure out what I want to do, I [heart]:

[illustrations: sketch of a house, outline of a house in dots]

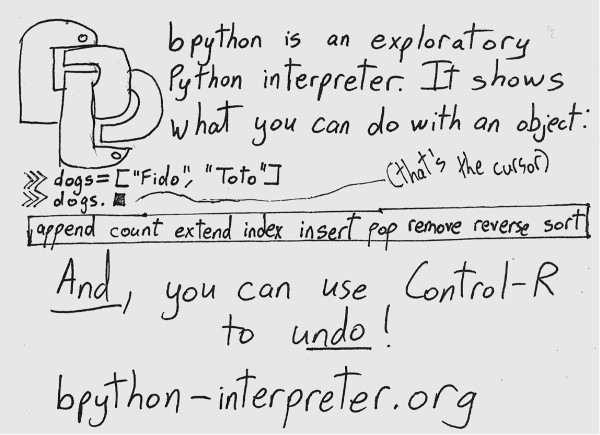

bpython is an exploratory Python interpreter. It shows what you can do with an object:

And, you can use Control-R to undo!

[illustrations: bpython logo, pointer to cursor after dogs.]

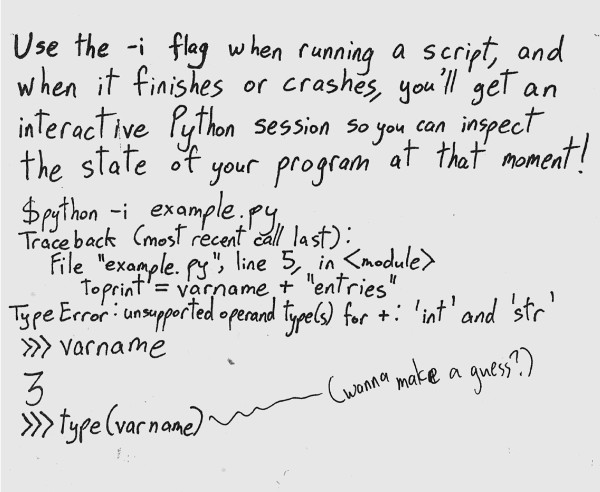

Use the -i flag when running a script, and when it finishes or crashes, you'll get an interactive Python session so you can inspect the state of your program at that moment!

[illustration: pointer to type(varname) asking, "wanna make a guess?"]

More: "A Few Python Tips"

CC BY-SA 2016 Sumana Harihareswara

Everyone has something to teach;

Here's the directory that contains those thumbnails, plus a PDF to print out and turn into an eight-page booklet with one center cut and a bit of folding. That directory also contains a screenshot of the bpython logo with a grid overlaid, in case you ever want to hand-draw it. Hand-drawing the bpython logo was the hardest thing about making this zine (beating "fitting a sample error message into the width allotted" by a narrow margin).

Libby Horacek and Anne DeCusatis not only volunteered at the MergeSort table -- they also created zines right there and then! (Libby, Anne.) The software zine heritage of The Whole Earth Software Review, 2600, BubbleSort, Julia Evans, The Recompiler, et alia continues!

(I know about bpython and python -i because I learned about them at the Recurse Center. Want to become a better programmer? Join the Recurse Center!)

2 of my favorite lenses

[magnifying glass and eyeglass icons]

by Sumana Harihareswara

bpython & python -i

>>> dogs = ["Fido", "Toto"]

>>> dogs.

append count extend index insert pop remove reverse sort

bpython-interpreter.org

$ python -i example.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "example.py", line 5, in

harihareswara.net/talks.html

This zine made in honor of

MergeSort

NYC's feminist makerspace!

http://mergesort.nyc

harihareswara.net @brainwane

everyone has something to learn.